Jane Austen and the Evolution of English Country Houses

by Ed Ratcliffe

This is a brief description of how the English country house evolved up to the time of Jane Austen, and some remarks on Jane Austen’s most unusual use of a house in her stories.

The English country house as we know it originated because the Duke of Richmond won the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. That battle ended the Wars of the Roses, and the long peace that followed eliminated the need for the fortified houses that had been common in preceding centuries. Thus the peace of the Duke (who became Henry VII) provided the opportunity for the English country house.

Henry VIII provided some of the materials for the houses when he dissolved the monasteries. About one-fourth of the land in England changed hands at the Dissolution. It was the largest transfer of ownership since the Conquest. Some of the thousands of religious buildings were simply converted to secular use – Donwell Abbey and Northanger Abbey, for instance. Others were quarried to provide the stone for new buildings. Some monastic real estate was sold to provide funds for building.

Elizabeth I provided important means for the great period of country house building. The decades of commercial prosperity and successful piracy in her reign made many Englishmen rich. Sir Francis Drake, the most successful pirate in history, brought home so much booty that Elizabeth could have paid off the national debt with her share alone. Francis Bacon said about Elizabeth that “she received a realm of cottages, and hath made a realm of palaces.”

Of course this oversimplifies what happened. There were a few great country houses before Henry VII – Haddon Hall, for instance – and the later ones were by no means all developed from monasteries. But most of the mansions we think of as typical were built during or after Elizabeth’s time with fortunes that originated or were greatly increased in her time, and often used monastic building materials or real estate.

What was the motive for building huge mansions like Wentworth Woodhouse, more than 600 feet wide? (That’s more than twice as wide as a football field is long). Very large houses such as these were primarily a display of power. They were meant to impress. A great house could overawe the neighborhood and knock the socks off a visitor. (Note that Wentworth Woodhouse was 600 wide, not 600 feet deep). Secondarily, great houses were a source of power.

Halperin’s biography of Jane Austen surprises us with this mention of Wentworth Woodhouse: “When the snobbish Sir Walter Elliot says of the hero of Persuasion, ‘Mr Wentworth was nobody … quite unconnected, nothing to do with the Strafford family. One wonders how the names of many of our nobility become so common,’ it adds to the piquancy of the satire that Jane Austen’s family was in fact ‘connected’ with the Strafford Wentworths, who, incidentally, were ancestors of the Earls Fitzwilliam, of Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire.

Households could be very large. One hundred and even two hundred people were common. Cardinal Wolsey had a mistress, several children, and five hundred people in his household. (Remember that this was a man who had taken a vow of poverty and chastity).

In earlier times, long before Wolsey, almost all members of the household were men. The only women were the lady, her daughters if any, and the women who attended them. It is impossible to believe that the scores or hundreds of men in these households led celibate lives, but their women do not appear in the records.

When women who did not serve the lady began to appear, in the 13th century, they were menial servants, used because they were cheaper than men. For centuries women servants were kept in the back of the house, out of sight of visitors. Men, especially tall men, appeared for visitors.

Travel in the early centuries was, in the best conditions, uncomfortable, slow, difficult, expensive, and sometimes dangerous. In the worst conditions it was literally impossible. Many diaries and letters show that mud, cold, and bandits could isolate a country house for months. One traveler in the 18th century (Jane Austen’s century) spoke of potholes five feet deep, but no vehicle had wheels ten feet in diameter. Those potholes were made by potters, digging up clay in the public road.

The difficulties of travel are reflected in certain attitudes of Jane Austen’s characters that may seem strange to us. In our time, when travel is easy and pleasant, we generally do not make social calls on casual acquaintances unless we have been invited to do so – we would consider such calls forward and intrusive. But the isolation of country life, even in Jane Austen’s time, could make such calls welcome, and the difficulties and expense of travel could elevate them to compliments. In Pride and Prejudice, when Elizabeth and the Gardiners are in Lambton, Mr. Darcy and his sister pay them an unexpected early visit. The narrator calls it “a striking civility.” When Elizabeth and the Gardiners make an uninvited return visit to Pemberley the next day, the narrator calls it an “exertion of politeness.” (Note that word “exertion”). And these visits were made over short distances in good vehicles on what appear to be good roads.

(Incidentally, when carriages began to appear in significant numbers in 16th century Europe, laws were passed in every country restricting their use to the upper classes. Lawmakers believed they would make the lower classes lazy).

How were the households organized? Until about the 14th century, the lord and all his followers had customarily, for many centuries, eaten their dinner together in the great hall of the house – a bonding process, in modern terms. But in that century a great change occurred: the lord and his family, and his important guests, moved upstairs to the lord’s bedchamber for dinner, and left their followers in the hall. They probably moved up because the first floor (second floor, American) was drier and more secure from attack, but the move was the beginning of a trend that continued for hundreds of years – the increasing separation of the lord, his lady, and their children from their followers. The move broke the sense of community and increased the sense of hierarchy. It also gave the lord and his family increased privacy. It did not give them informality.

Quite the contrary. The increased sense of hierarchy led to increased ceremony. Very careful distinctions were made in seating guests at the dining table upstairs. High-ranking guests were seated to the right of the lord in a section of the table called “the reward.” Lower-ranking guests were seated to the left, beyond the salt-cellar, in an area called “the board’s end.” (The phrase “below the salt” appears to be a modern term). The protocol was rigid: If there was only one guest fit to sit at the lord’s table, and he was a low-ranking guest, the lord would sit in solitary splendor at the middle of the table, with the lowly guest isolated at the board’s end. Conversation was impossible, but dignity was preserved. There are records of 20 servants who did nothing at dinner but prepare the lord’s place setting and serve his meal – 20 men served one man.

Over the next century or so, the combined bedroom-dining room upstairs became the largest and most important room in the house. It was called “the great chamber”.

Some of the ceremonies that developed in that period are almost beyond our belief. In one case an English queen was being re- introduced to society after giving birth. Part of the process was a dinner involving the queen and female guests. The queen sat alone at a table and the guests all knelt on the bare floor. The dinner took three hours and was held in absolute silence. No one spoke a word. The guests knelt on the bare floor for three hours.

In 1400 a country house contained one community. By 1800 it contained two communities. In 1400 when a lord spoke of his family he meant everyone who lived under his roof. By 1800 he meant his wife and children. By 1800 the lord’s followers had been transformed into what Jane Austen’s stories show them to be. They are like furniture: they are useful, they are taken for granted, and they are excluded from private family matters.

This great change in the meaning of “family” occurred for several reasons, but the chief was economic: in 1400 the great country house and its estate were almost the only source of power and wealth. By 1800 there were more important sources – government, law, commerce, industry, and the professions, for instance. When the country house declined in importance, so did the people who supported it.

The evolution of the country house from the 14th century to Jane Austen’s time can be traced by looking at the evolution of certain rooms – the parlour, the closet, the withdrawing room, and the library.

Early in the 14th century, French monasteries began to set aside a special room for visitors. It was always on the ground floor, with easy access from the outside of the monastery, and rules were relaxed there. It was a place where visitors could come and talk with the monks. The room was called a “parlour” – a place for talking. When the English upper classes heard about such rooms they adopted them enthusiastically, doubtless as a means of escape from the stifling formality of their lives, and by the end of the century there were many parlours in English country houses. Parlours were simply informal rooms where the great ceremony that surrounded lords and ladies was relaxed. There might be a summer parlour on the north side of a house, a winter parlour on the south side, a great parlour directly under the great chamber (and just as big), a breakfast parlour, a dining parlour, a parlour used as a guest bedroom, a parlour used as a visiting room for guests not important enough to bring into the great chamber, and so on and on. Most of the rooms that developed in English great houses of later times were derived from the parlour: billiard rooms, gun rooms, game rooms, writing rooms, morning rooms, breakfast rooms, dining rooms and others. Jane Austen, writing about 1800, uses “dining-parlour” as often as she uses “dining-room” and “breakfast- parlour” as often as she uses “breakfast-room.”

The closet was not a derivative of the parlour and had a long and important history before it descended to become a place where we store brooms and mops. An early closet was simply a small room that was closed in a special sense. Until about the 15th century, the lord and lady had no privacy from their followers. But followers in the household had by this time begun their descent from family members, to household members, to servants. The master-servant relationship seems to have taken on a special quality: servants “weren’t there” in a certain sense. The lord or lady might undress before a servant as casually as before a dog or cat.

In earlier times a personal servant could enter any room at any time he needed to, without knocking, and whether he had been called or not. After all, he was a member of the family. But late in the 15th century some lords and ladies began to want more privacy from their servants, and made a rule about it. The rule was simply that no servant could enter a certain room, called a closet, unless he had been called for. Closets became private rooms used for devotions, study, business, discussions with family or advisers, and so forth. Because closets were often used for devotions, they were sometimes combined with the chapel. The family would sit upstairs in the closet, which had become a balcony of the chapel, and the servants downstairs. Jane Austen saw such an arrangement in Stoneleigh Abbey, a great house belonging to a relative, and later described just that kind of chapel at Sotherton in Mansfield Park.

It is sometimes said that there was no privacy in medieval houses, there were no hallways, and people might have to go through several other people’s bedrooms to get to their own. That idea seems to be based on a misreading of the architecture. A suite of rooms with no individual access to a hallway was not a set of bedrooms, but the private suite of a lord, who might have as many as seven or eight rooms to himself. But even in such a suite there could be no privacy from servants until closets were invented.

Incidentally, the suite of rooms used by the lord was sometimes called the “axis of honor,” and the depth of a visitor’s admission into it was a measure of his importance.

The lord might do a number of things in his suite of rooms, but reading was probably not one of them. Printing was developed in the middle of the 15th century, and Jaques Barzun writes that by the end of that century, around 1500, “roughly nine million volumes” had been printed. Very few of these found their way to England. English libraries did not begin to appear until about a century later, and then only in houses of the higher clergy, where literacy was greatest. In Henry VIII’s time a certain gentleman wrote as follows: “I’d rather that my son should hang than study letters . . . the study of letters should be left to the sons of rustics.”

In Elizabeth’s time a countess, Bess of Hardwick, was the richest woman in England after the queen. She was highly intelligent, shrewd, and the builder of a great mansion that is still one of the showplaces of England. She owned six books.

The oldest surviving English library was built a couple of decades later, in 1620, in a parish church at Kederminster. Mr. Darcy said that his family library had been “the work of many generations,” so it may have been a couple of hundred years old. In that case it would have been one of the earliest English libraries.

Now what were withdrawing rooms?

The proliferation of rooms in great houses produced a great many minor rooms called withdrawing rooms. They were just little rooms, off larger rooms, where people could have more privacy than in the large rooms. Any important room could have a withdrawing room attached to it, and they became very common in country houses.

By about 1600 it had become customary for the lord and lady to invite some of their guests into a withdrawing room for conversation after dinner. By 1650 that room had come to be called the “drawing room.” By the end of the century another custom had developed: At the end of the meal ladies withdrew from the dinner table before the gentlemen and went to the drawing room, where the gentlemen joined them later. No one seems sure how this custom originated. It was not described by Pepys in the 1660s. But in a play written by Congreve in 1694 the women are described as “at the end of the gallery, retired to their tea and scandal, according to their ancient custom, after dinner.”

By the 18th century the drawing room had become the major room of the house, larger than the dining room. (Note the historic progression of the major room of the house from great hall to great chamber to drawing room, a process of increasing exclusivity). Sometimes the women spent several hours in the drawing room waiting for the men. The drawing room thus came to be thought of as a woman’s room and the dining room as a man’s room, and the rooms were often decorated accordingly.

We see this reflected in Emma, at the Christmas eve dinner party at the Weston’s house. Mr. Elton says, in a carriage approaching the house, “Mr. Weston’s dining room does not accommodate more than ten comfortably,” and on the next page the narrator says, “they walked into Mrs. Weston’s drawing room.”

Only one other kind of room could be socially more important than the drawing room, and that was the saloon. It was the last important room to appear in the country house – the first quotation for “saloon” in the OED is dated 1728. A saloon occurred only in the greatest houses, and was always the largest and grandest room unless there was a ballroom. In Jane Austen’s stories, only one house has a saloon: Mr. Darcy’s Pemberley, the grandest house of all.

We’ve seen how the parlour brought informality into the country house. Now let’s consider a later source of informality. Think of how the political world must have looked to an Englishman in 1714, when George I came to the throne. Within the previous 70 years, within living memory, (1) the English had beheaded a king, (2) they had lived 11 years without a king, (3) they had carried out two successful revolutions, and (4) they had invited two changes of dynasty. And they had come out of that turmoil just fine. After all those changes they couldn’t take authority as seriously as they used to do. The French could talk all they wanted to about the divine right of kings, but the English weren’t listening.

Their new feeling of freedom expressed itself in an informality of many kinds: in portraiture, dress, and speech, as well as in landscape, architecture, and society. The 17th century had been the century of rigidly formal gardens, copied from the French. Such gardens were so expensive to build and maintain that they bankrupted a few rich Englishmen. But early in the 18th century the informal English garden appeared.

The term “wilderness” had meant untouched nature, but by 1650 it also meant a carefully planted small forest where ladies and gentlemen could walk in a safe simulation of the wild, as they did at Sotherton. About a century later shrubberies appeared, small-scale wildernesses used especially for genteel walking, as at Hartfield, Cleveland, and the parsonages at Mansfield Park and Delaford.

Ha-has, or sunk fences, were invented to provide an uninterrupted view across a lawn while preventing cattle from approaching the house. Reality was distorted – a pasture was made to look like part of the lawn. In Jane Austen’s stories a ha-ha appears only at Sotherton, where Jane, excellent artist as always, uses it repeatedly to symbolize psychological restraint.

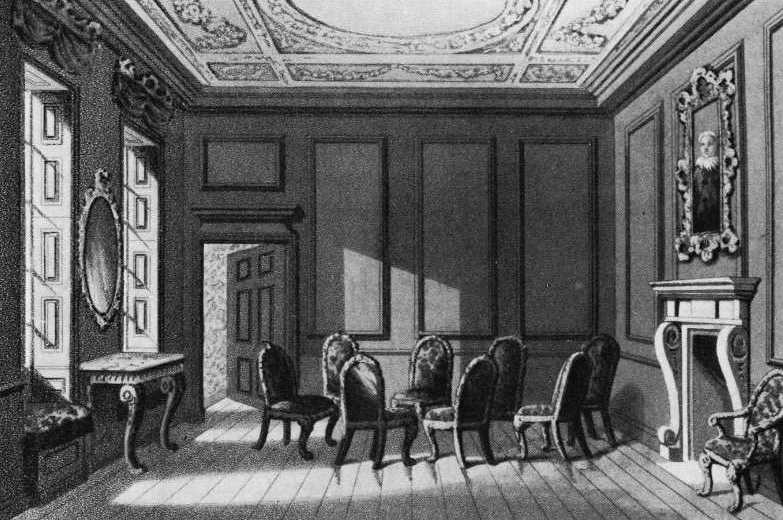

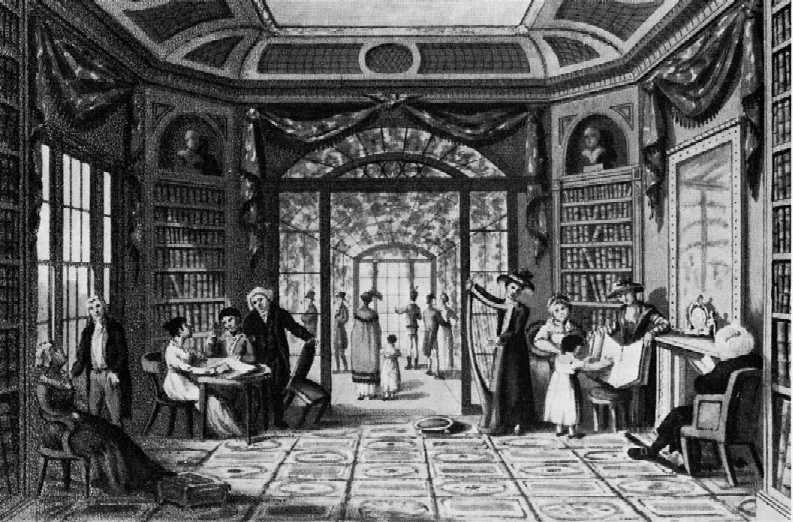

Remember Humphrey Repton, the real-life landscape architect who is mentioned in Mansfield Park? He advocated informality inside the house as well as out. Here are two “before-and-after” pictures he drew to show how a parlour with an old-fashioned family circle should be converted into a modern living room.

Many families of the 18th century actually had such a circular arrangement of chairs. Jane Austen mentions either a literal or figurative family circle in three novels. Notice that only one group of people is indicated here.

Now here’s Repton’s idea of how the room should look. You can count as many as eight groups of people in the living room and just outside.

About 1750 a new and informal style of social gathering appeared. It was called an assembly, and consisted of “a meeting of polite society for talking, playing cards, drinking tea, and dancing.” What was new about that? Simply that different groups of people at an assembly could do different things at the same time. Until then social life had been so formal that everyone at a party had to do the same thing at the same time. Even the name “assembly” seems to imply an informal gathering. The informality of the assembly made it very popular, and public assembly rooms sprang up all over England, each with its own ballroom, tearoom, and cardroom, where (gasp!) three activities could take place at the very same time.

Bath, a fashionable resort, had three sets of Assembly Rooms in the late 18th century. In the Upper Assembly Rooms Anne Elliot stopped Captain Wentworth dead in his tracks at the concert shortly before his second proposal. Catherine Morland was introduced to Bath society in the same rooms.

Other expressions of informality were the country houses with no facades. These began to appear late in the 18th century, when Jane Austen was a girl. Instead of being equipped with columns and pediments and such things that had been common in great houses, some houses looked nearly the same from the front and the sides, and not too different in back.

An extreme architectural expression of the new informality was the cottage ornee such as we read about in Sanditon. A small survivor exists today in Lyme Regis. One writer said the cottage ornee allowed its owners to “live the simple life in simple luxury in a simple cottage with – quite often – fifteen simple bedrooms, all hung with French wallpaper.”

About the time Jane Austen was born a system of bells was invented to call servants, so that they almost never appeared unless they were summoned. From being members of the family they had descended to being creatures who appeared on command.

Jane Austen lived more than half her life in the Steventon Rectory, a crowded house so dilapidated that it was torn down eleven years after her death. Money was so scarce that her father took in boarding students and sometimes borrowed money from relatives to meet living expenses. It may have been here that Jane decided that it was wrong to marry for money, but foolish to marry without it.

By the way, the word “dilapidation” occurs in a strange statement in Mansfield Park: “Dr. Grant and Mrs. Norris were seldom good friends; their acquaintance had begun in dilapidations.” A new incumbent in a parish could by law require the previous incumbent to pay for any damage to a rectory or church that had occurred during his incumbency. The money paid for repairs was called a “dilapidation.” Apparently Mr. Norris had paid more than one dilapidation to Dr. Grant, and when we remember how careful Mrs. Norris was with money, we can see a source of friction.

On one occasion Jane visited her brother in Kent and was invited to a grand house called Goodnestone, a mile away. She wrote to her sister about the evening. “We dined at Goodnestone and in the evening danced two country dances. I opened the ball with Edward Bridges.” After some details, she concludes as follows: “We supped there and walked home at night under the shade of two umbrellas.”

Her account of the evening is short and simple, but consider what it tells us about contemporary manners. She was honored by opening the ball with the son of the house, but when she left, she was made to walk, in the dark, in the rain, on a muddy path, probably near midnight, a mile back to Rowling. The incident may have inspired Sir Thomas Bertram’s indignant response when it was proposed that Fanny Price walk to a dinner engagement:

“Walk!” repeated Sir Thomas, in a tone of most unanswerable dignity, and coming farther into the room. – “My niece walk to a dinner engagement at this time of the year!”

Now I want to discuss Jane Austen’s most unusual treatment of a house. It occurs in Persuasion. You will remember that Sir Walter Elliot and his daughter moved to Bath and took a house in Camden Place, a lofty and dignified position that befitted a man of consequence. Mr. Elliot, the cousin, had arrived in Bath shortly before Anne.

Jane Austen tells us where Admiral Croft lived in Bath, where Lady Russell lived, where Colonel Wallace lived, where Mrs. Smith lived, where Lady Dalrymple lived, even where Nurse Rook lived. In fact, she tells us where every single character lived in Bath – except Mr. Elliot, a major character.

This is remarkable. We know where even the minor characters live, who never appear in person and are never quoted directly, but we hear not one word about Mr. Elliot’s house or its location.

Mrs. Smith, for example – who is dragged into the story by the scruff of her neck for the sole purpose of destroying Mr. Elliot’s reputation – lives in Westgate Buildings. Jane Austen makes it abundantly clear that Mrs. Smith is poor. It was not necessary to tell us that she lived in the low-rent district of Bath. But Jane does tell us. She even tells us where Mrs. Smith’s nurse lived – she who was merely a conduit for gossip from Marlborough Buildings to Westgate Buildings. I wonder if Jane lists so carefully the houses of all the other characters in order to emphasize her total silence about Mr. Elliot’s house.

We never hear of Mr. Elliot in his house, going to his house, or coming from his house (except once, obliquely: “It was possible he might stop in his way home . . .”). Not a word of description of the house. No one ever goes to visit him. No one ever talks about his house. No one even thinks about his house.

Why did Jane Austen omit all reference to Mr. Elliot’s house? The only answer I have thought of is this: We all know that she used her houses to imply the characteristics of the people who lived in them. I believe she uses her silence about Mr. Elliot’s house (his “background”) to intimate, very subtly and well before we know it, that Mr. Elliot is a man of mystery. We know almost nothing about him, although we think we know all that is important. Sir Walter, Elizabeth, and Lady Russell were delighted with him. Only Anne Elliot had doubts.

Note the way he is introduced to us in Bath. Late in the evening of Anne’s arrival in Bath, there is a knock on the door. No sound of footsteps, no approach of a carriage or a chair. Just a knock. Out of the darkness and silence of the night, he appears. At the end of his visit, he disappears. Not one word about his departure. He simply vanishes from the narrative until the next chapter.

Jane described other houses artfully, to show us the characteristics of the owners or visitors. Here she carries art a step further by total silence about a house. She may have had deeper reasons or other reasons than this, but this is the best I’ve thought of so far. (Any comments?)

Jane Austen was not interested in architecture. Houses were important only as they helped her present the characteristics of her people and show them in action – sad at a farewell breakfast, happy at a Christmas dinner, anxiously consulting a family lawyer, or delighted with a proposal of marriage.

As we move farther into the 19th century, beyond Jane Austen, we find that the great age of country house building is past. The architecture of 19th century country houses became derivative, even imitative, and sometimes, to our eyes, ridiculous. Great houses of the past were symbols of earlier power, but no longer sources of power or generators of wealth. Power lay elsewhere, and wealth was consumed in maintaining houses now centuries old.

Copyright © 2001 by Edward Ratcliffe

Before retiring, Ed Ratcliffe was a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, doing computer simulations of physical processes. He became interested in Jane Austen in 1980 when he saw the BBC-TV production of Pride and Prejudice. He joined JASNA and JASNA NorCal in 1981.