Ireland in the Time of Jane Austen

by Joan Duffy Ghariani

Presented at the 2002 Annual General Meeting of the Jane Austen Society of North America.

The idea for writing about the connection between Jane Austen’s world and Ireland came from something that Miss Bates said. I will give the quotation later in this paper.

Most of the eighteenth century in Ireland was a time of relative calm and peace. The so-called “Ascendancy,” the Anglican (that is, Church of Ireland) minority, was in complete control, and the native Irish and the Old English, mostly Catholic, were crushed and powerless, deprived of land, political power, higher education, and entry to the professions. Profound changes were afoot in Jane Austen’s lifetime, changes that have impacted Ireland to the present day.

I use the words “Catholic,” “Protestant,” “Anglican” and “Presbyterian” because I have to; they represent the realities of the time. If I were writing about Northern Ireland today, I would say Unionist and Nationalist, but these terms do not apply until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The terms “Old English” and “Anglo-Norman” mean those English who had been in Ireland before the Tudor plantations, and who had amalgamated with the Native Irish. “Plantation” means the process of moving the Native Irish and the Old English off the land and replacing them with Protestant English and Scottish settlers.

I will first deal with the events that set the scene for the eighteenth century, and then go forward to about 1850. Jane Austen died young; she could easily have lived until 1850, so it seems reasonable to cover that period briefly.

The English monarchs had claimed lordship over Ireland since the Anglo-Normans had first invaded in the twelfth century, but the Anglo-Normans and the Gaelic Irish became one very quickly, and enjoyed almost complete independence, except in Dublin and the area around it which was called the Pale. The Tudor monarchs set about regaining control of Ireland by force of arms and by plantation (Coohill 18). Independent Ireland suffered three massive blows in the seventeenth century. The first was in 1603 when the last Gaelic chiefs and their Spanish allies were defeated (Moody and Martin 188). The chiefs and their followers departed for Spain and that left Ulster, the northern part of Ireland, unprotected. Ulster was planted with Presbyterian Scots. They are some of the ancestors of the present-day Ulster Unionists.

The next attempt to wrest control of Ireland from the English came in the middle of the seventeenth century (198). The Irish, the Old English, and some of the Presbyterians rose in rebellion when the conflict started between Charles the First and the English Parliament. Many Protestants were killed. The rising ended when Cromwell led an army to Ireland and waged a genocidal campaign. The Catholic landowners were dispossessed, and in theory were given lands in Connaught and ordered to move west of the Shannon before May 1653. This became known as “To Hell or to Connaught,” because those who did not move would have been killed, and the Puritans really believed that they would all go to Hell. Of course, the Catholics probably believed the same of the Puritans.

The last defeat came when then James the Second and his son-in-law William of Orange arrived in Ireland to fight it out for the English throne (209). William prevailed with the help of the Presbyterians and that is the victory that the Orangemen celebrate to this day, marching and beating huge drums on July twelfth.

The behavior of the Stuart kings towards Ireland did not really merit any loyalty or support from the Irish, but I suppose they appeared marginally better than the Puritans or the unknown policies of William the Third.

William meant to keep his side of the Treaty of Limerick made between the combatants in 1691. But the English Parliament, now triumphant over the crown, and the Irish Parliament, now all Anglican, did not ratify the treaty and were now determined to squash the Catholic Irish for good. The Irish fighting men had sailed away with their French allies, and any prospect of resistance was over.

We should note that all the rebellions in the seventeenth century involved foreign help from France and Spain, so Ireland was regarded as a possible entryway for any of England’s enemies. The Irish Parliament passed a series of laws known as the Popery Code or the Penal Laws (Coohill 26). These laws imposed oaths that Catholics could not in conscience take, and so they were barred from Parliament, from the professions, and from holding commissions in the Army or Navy. They were also forbidden to open schools or to send their children abroad for education, or to carry arms.

The laws against Catholics buying land or holding leases longer than thirty-one years reduced the amount of land held by them from fourteen percent in 1700 to hardly five percent in 1778. Of course, many landowning families changed their religion. The Penal Laws applied also to Presbyterians and other Dissenters, to a lesser degree. The aim was not really to change the people’s religion but to deprive them of all power. Only a few devout Protestant clergymen and evangelical societies (including the Quakers) cared about the souls of the Irish. So, when the anti-Catholic feeling had died down a bit, and the country had been at peace for a while, the laws were relaxed. From about 1720, Catholics could quietly practice their religion. The priests and bishops were illegally in the country but were not tracked down unless a pursuivant — what we would call a bounty hunter — set out to get them. So they were cautious, dressed as middle-class gentlemen, were called Mister, not Father, built “chapels” (they were not allowed to call them “churches”) in back streets, and preached obedience to the law, saying that all authority came from God. They encouraged their flock to look to the next life for justice and happiness.

The Scottish Parliament was abolished early in the eighteenth century, and Scotland, England, and Wales became Great Britain, so that is now the correct term to use.

By the time Jane Austen was born in 1775, Ireland had been relatively peaceful for over eighty years. As Jane Austen came from a clerical background, I will write a bit about Church of Ireland clerical life, using as examples people that she would probably have heard of. Jonathan Swift, (1667 to 1745) was Dean of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin (Moody & Martin 205,221). He regarded himself as Irish and was deeply sympathetic towards the wretched lives of the poor. He left a legacy to found a mental hospital in Dublin. It is called Saint Patrick’s and is still in existence and has an excellent reputation. But he was very disappointed that he ended up in Dublin; he would have preferred a lucrative living in England where he would have moved in a more glittering and powerful society. His name will live on because he wrote “Gulliver’s Travels.”

George Berkeley was born in Ireland in 1685 and died in Oxford in 1753 (Berkeley & Warnock 7-9). He was one of the foremost philosophers of his era and his works are still in print. He spent a lot of time outside Ireland, some of it in Rhode Island attempting to establish a missionary college in Bermuda. He failed and, leaving his books to Yale, returned to Ireland where he was appointed Bishop of Cloyne. He appears to have carried out his duties conscientiously for eighteen years until his death. However, he had been Dean of Derry earlier in life, for the ten years between 1724 and 1734, and had never visited his Deanery at all. So he was one of those clergymen who drew an income and had someone else do the work. The city of Berkeley in California, the site of the famous University of California campus, is named after him.

Oliver Goldsmith (1728 to 1774) is another person of whom Jane Austen would have heard. He was born into a Church of Ireland family in Ireland (Wibberley 7-225). His father, his maternal grandfather, and his maternal granduncle were all ministers. When the time came for Oliver to go to Trinity College in Dublin, his father had an income of two hundred pounds a year, and that should have been adequate. But his father spent or gave away most of his income and had no savings. So, like Mr. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, when it became necessary to provide a dowry for a daughter he did not have much money (308). He signed a contract promising to pay, in the future, four hundred pounds, two years’ income. Oliver had to go to Trinity as a sizer, a student who is also a servant. This was a bitter blow for him. He left Trinity without a degree but did subsequently get some sort of a degree in medicine and was called “Doctor.” He ended up in London as a writer, finding it hard to make ends meet he had his father’s habit of giving away his money. Jane would have been familiar with some of his works, The Deserted Village, The Vicar of Wakefield and the play She Stoops to Conquer. In fact, we are specifically told in Emma (29) that young Mr. Robert Martin had read The Vicar of Wakefield.

Most Janeites find the brief story of Jane Austen and Thomas Langlois Lefroy (1776 to 1869) fascinating (Austen-Leigh & Le Faye 85-87). Maybe she was a little in love with him and he with her. You may be interested to hear more about Thomas Langlois Lefroy. He did marry well, and did have a long and successful legal career in Ireland. The following information is from a book by F. Erlington Ball (354 – 355). We are told that he was “called to the Irish Bar in 1797, married Mary, only daughter and heiress of Jeffrey Paul of Silver Spring, County Wexford in 1799, published / edited legal texts, followed the Munster circuit for some years, afterwards did equity practice only, became a King’s counsel in 1816, was presented with the freedom of Cork in a silver box in 1825, became a doctor of laws in 1827, was a conservative in politics, was elected member of Parliament for Dublin University (Trinity College) seven times, erected a country seat at Curryglass, County Longford, was promoted to the chief justiceship, resigned his seat on the bench at the age of ninety, died in 1869 at his other residence Newcourt near Bray, and was remarkable for the strength of his religious convictions.” We are told that he “was an evangelical Churchman of the most pronounced type who had expressed detestation of Catholic Emancipation” (288). Catholic Emancipation, which I will explain elsewhere, was certainly opposed bitterly by many, including George the Third, over many years, but by the time it was passed in 1829 it was obviously essential to Britain’s ability to govern Ireland, and so opposition to it was no longer as acceptable as it had been.

If Jane Austen and Tom Lefroy had been able to marry, would she have been happy? I think that she would have been able to accept his extreme conservative and evangelical views, as long as he stayed in the Anglican Church, which he did. Maybe the terrible poverty she would have seen in Ireland would not have horrified her as it did Jonathan Swift. In Emma, Jane Austen gives a lovely description of Emma’s compassionate attitude towards the poor and says Emma “always gave her assistance with as much intelligence as good-will” (86). But then Emma says, “If we feel for the wretched, enough to do all we can for them, the rest is empty sympathy, only distressing to ourselves” (87). But doing “all we can” is subjective, and Emma does not suffer any real financial deprivation from the help she gives the poor. I see Jane Austen as able to live in Ireland, in the upper middle-class, prosperous circle that was Tom Lefroy’s, do her duty and bring up her children, but I do not see her as having time and opportunity to write novels, let alone get support and approval from her husband to do so.

The political situation in Ireland in Jane Austen’s lifetime was very dynamic and complicated and can only be summarized in this paper. There were many different groups, each with its own agenda.

A Catholic middle-class was emerging in the cities and demanding relief from those penal laws that were still in force. The Presbyterians in Ulster felt that the British Navy could no longer protect them in case of invasion (Fitzgibbon 67-68). This was because, in 1778, Britain being at war with America and France, the American sea captain John Paul Jones sailed the U.S.S. Ranger into Belfast Lough, where he fought and captured a British warship, H.M.S. Drake, and took her as a prize to Brest.

The Presbyterians were also angry because of the remaining penal laws that applied to them. They emigrated in great numbers to North America (47-48).

There was growing agrarian violence because of an increasing population and struggles for land. The American and French revolutions profoundly affected the country both in practical and ideological ways (Moody & Martin 232-236). Practically it led to the removal of British troops to fight in America. They were replaced by homegrown Protestant militias that the British government did not control. These militias became the United Irishmen, from both the north and the south of the country, and ultimately sought French help and rose in rebellion. Before that happened the Irish Parliament gained greater independence for itself. In 1782 most of the legislation that made the Irish Parliament subservient to the British Parliament was repealed. This was a great source of pride and pleasure to the Irish Anglicans, but they were still not willing to admit Catholics. This short-lived Parliament (1782 to 1800) is known in history as Grattan’s Parliament after its most eloquent and effective member, Henry Grattan. The Jacobin and revolutionary fervor generated in Ireland by the French and American revolutions called for liberty, equality, and political independence.

At first it was thought that these could be achieved by peaceful means, but the British government was hampered by its fear of foreign invasion and by the intransigence of the Irish and British Parliaments. It tried conciliation mixed with repression. The end result was the Rising or Rebellion of 1798. One French fleet with troops had attempted an invasion in 1796 but was scattered by storms, having evaded the British Navy (Fitzgibbon 119-120). In 1798 another group of French succeeded in landing but was quickly defeated, and a third fleet was captured at sea by the British Navy.

The rebellion planned for 1798 was badly coordinated and turned into isolated skirmishes. The rebels were defeated and many were executed. Local Protestants were killed by the insurgents. The total death toll is estimated at about thirty thousand. The end result of all this was that the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, decided to abolish the Kingdom of Ireland and set up the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. He persuaded the members of the two houses of the Irish Parliament to vote for union by bribing those who were reluctant with pensions, peerages, and places that is, jobs. To give them their due, many believed it would be the best solution. It would abolish the trade restrictions that hampered Ireland’s commerce and would bring free trade. Catholic Emancipation was also implicitly promised but was not achieved until 1829.

The Act of Union came into effect January 1, 1801. Ireland was allotted one hundred of the six hundred odd seats in the Westminster Parliament and Dublin ceased to be a capital city. What part, if any did Jane Austen’s brothers play in this period in Ireland? Her sailor brothers were not involved in fighting the three French fleets that tried to invade the country (Hubback 21-57), but her brother Henry was sent to Ireland with his regiment in 1799 in the wake of the 1798 rebellion. He was there for seven months (Tomalin 152). The Irish Catholics, led by Daniel O’Connell (1775 to 1850) spent the years 1801 to 1829 agitating by legal means for emancipation. They finally achieved it and were able to sit in the House of Commons (O’Ferrell 15-65). They then started campaigning to repeal the Union, again led by Daniel O’Connell (68-131). They did not succeed. O’Connell lived to see the Great Irish Famine, and died broken-hearted in 1847.

And now a few comments on other aspects of Irish life in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many beautiful buildings went up in Dublin including the Four Courts the law buildings and the Custom House, both on the River Liffey (Moody & Martin 240-242). Lovely squares of Georgian houses were built. After the Act of Union the nobility and aristocracy basically moved away to the center of power London. Some of these houses were taken over by the new upper class doctors and lawyers and some became terrible slums which were not cleared until the nineteen fifties. Leinster House, the town house of the Duke of Leinster, the premier Irish peer, is now the Irish Dáil or Parliament, and the original House of Parliament is now the Bank of Ireland.

The oldest general hospital in Ireland, Dr Steevens’s Hospital, was founded in Dublin in 1733, funded by a bequest from Richard Steevens (Craig). He was the son of an English immigrant of the Commonwealth period. The hospital was still there when I was growing up. In recent years it has become part of the Regional Hospital System.

In 1757, Dr. Bartholomew Mosse opened one of the first maternity hospitals in the world, the “Rotunda”, north of the Liffey (Craig). It is still there and has an excellent international reputation. Dr. Mosse raised the money for it by lotteries, plays, concerts and oratorios, and some of this aspect also lives on. The Gate Theatre is still part of the complex. Both Richard Steevens and Bartholomew Mosse had a deep love of their fellow men, and a great sympathy for the poor.

In spite of the many problems, the period was one of expanding commerce. Agricultural produce was in demand during the wars with America and France. Canals were built, the Grand Canal and the Royal Canal, connecting Dublin to the Shannon (Moody & Martin 234). The population grew rapidly, because armies no longer ravaged the land and destroyed the crops. Potatoes, the main sustenance of the poor, are a complete food when combined with milk, and potatoes were easily grown and produced more food per acre than any other crop. The country people also had a plentiful source of heat peat, called turf in Ireland.

The Irish Gaelic language was losing ground to English, and was spoken mainly by the rural population (Ó’Murchú 25). But much folk poetry was still being written in Irish Gaelic (O’Tuama & Kinsella 13).

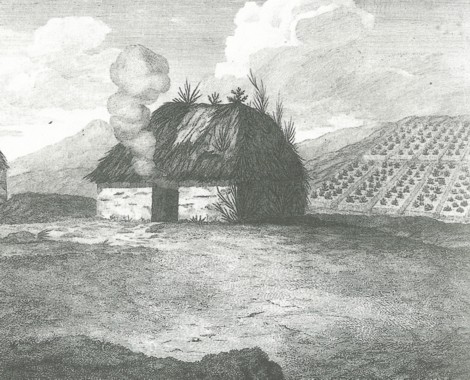

The houses of the rural Irish tended to be one-room cabins. We have a reproduction of one from Arthur Young’s “Tour in Ireland,” 1780 (Bartoletti 6).

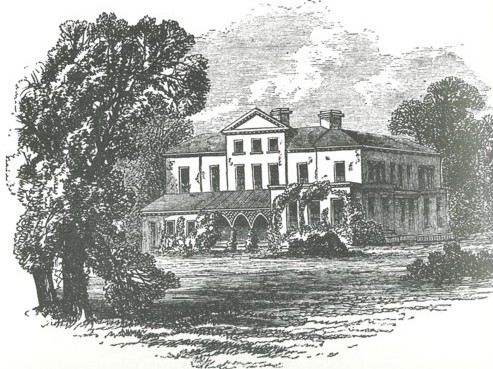

This is a reproduction of the home of Maria Edgeworth’s family from Irish Pictures, London Religious Tract Society 1888 (20). The contrast between the two is telling.

And now we come to deal with some of the references to Ireland and the Irish from Jane Austen’s works. In The Watsons there is a discussion between Emma Watson and her host Mr. Edwards. We learn that Emma’s aunt has married an army officer, Captain O’Brien and gone with him to Ireland. Mr Edwards says “I do not wonder that you should not wish to go with her into that country, Miss Emma” (326). Later on Emma’s brother Robert Watson says “A pretty piece of work your Aunt Turner has made of it!” (351). Captain O’Brien is obviously regarded as a fortune hunter, and the marriage as likely to be very unfortunate for his wife. The Watsons was written in 1804, soon after the 1798 Rebellion that accounts for Mr. Edwards’ remark at this stage Jane Austen may have regarded Ireland as a dangerous place to live. If Captain O’Brien was a Catholic the penal laws would have prevented him from rising in his profession he could never have become a Colonel. So he may have been on the lookout for a rich wife. His still being in the army as a Captain suggests that he was a good bit younger than his wife.

In Persuasion we get an unflattering picture of the Dowager Vicountess Lady Dalrymple and her daughter Miss Carteret. “There was no superiority of manner, accomplishment, or understanding” and “Miss Carteret, with still less to say, was so plain and so awkward, that she would never have been tolerated in Camden-place but for her birth” (150). The text suggests that the title is old, not one of those conferred as a bribe to pass the Act of Union, but the depiction of these cousins may partly reflect the loss of respect for Irish titles which the new creations generated, and may also reflect the ambiguous position of the Anglo-Irish. In Ireland they were regarded as English, and in England they were regarded as Irish. Of Captain Wentworth, Lady Dalrymple says “A very fine young man indeed! More air than one often sees in Bath. Irish, I dare say” (188). Is this just Lady Dalrymple’s partiality, or a reflection of the tendency to see Ireland and the Irish as “the other” to whom traits and attributes both good and bad can be assigned, or is it a lingering memory of Tom Lefroy? The miniature of him painted by Engleheart shows him to have been handsome (Cecil 74).

Frank Churchill gives us an example of the tendency to ridicule the Irish, in Emma. He says that Miss Fairfax has done her hair in a very outrée fashion. “I must go and ask her whether it is an Irish fashion” (222). In Mansfield Park Maria Bertram is angry because her sister Julia and Henry Crawford so much enjoyed their trip to Sotherton. Henry says “Oh! I believe I was relating to her some ridiculous stories of an old Irish groom of my uncle’s.” Then he says “I could not have hoped to entertain you with Irish anecdotes during a ten mile drive” (99). In Jane Austen’s time the ethnic jokes were pretty savage and they were mostly directed against the Irish.

In Emma, Miss Bates makes the remark that first interested me in the subject of this paper. We hear that Jane Fairfax’s guardians, the Campbells, are going to visit their daughter in Ireland. The picture sketched of the Dixons’ life in Ireland is a peaceful and happy one. Ballycraig was probably beautiful; the word is Gaelic and means a home or townland on a mass of rock forming part of a cliff or headland, so the place was by the sea. Miss Bates says of Mrs. Dixon that she was impatient to see her parents” for till she got married last October, she was never away from them as much as a week, which must make it very strange to be in different kingdoms, I was going to say, but however different countries” (159). This sums up accurately the effect of the Act of Union 1801. It gave me great pleasure to see that Miss Bates was intelligent and read the newspapers with understanding. Miss Bates tells us that the Campbells were crossing from Holyhead in Wales to Dublin. The boats carried the mail as well as passengers, and the service was efficient. Emma wonders as to the “expedition and expense of the Irish mails” (298). She could have been told that the service was very good also.

The Irish car mentioned during the outing to Box Hill (374) was also known as a jaunting car. It had two long benches with guardrails, one on each side, facing outwards, and was used to drive visitors in places of scenic beauty such as the Lakes of Killarney.

We are told that a set of Irish melodies came with the mysterious new piano in Emma (242). In Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennett, playing the piano, “was glad to purchase praise and gratitude by Scotch and Irish airs” (25). Jane Austen copied out some Irish airs for her own use. Her interest may have had something to do with Tom Lefroy, but also may have been due to timing.

The following account is from “Ireland of the Welcomes” magazine. In the eighteenth century the Irish harpers were a dying breed, and their music was in danger of being lost. Some Belfast gentlemen decided to make an effort to record it. They issued a general invitation to all traditional harpers to gather in Belfast July 10 to 13, 1792, and promised that some remuneration would be given to all. Ten Irish harpers, one woman and nine men, and one Welshman came, and for three days performed their music. The person appointed to record it was a young student, Edward Bunting. It was an inspired choice. He worked on the transcriptions for the rest of his life and his first collection of “The Ancient Music of Ireland” was published in 1796. Celtic music today is very popular worldwide and owes a great debt to Bunting. In 1992 a bicentennial International harp festival was held in Belfast not eleven harpers but hundreds.

Out of the work of Edward Bunting came the life work of Thomas Moore. He composed the lyrics to go with the Irish melodies and his first publication was in 1808. Among his songs that have lived on to the present day are “The Last Rose of Summer” and “Let Erin Remember the Days of Old.”

If you are interested in the life of Thomas Moore, patriot, poet, ecumenist, singer, lover of humanity, and devoted friend one of his friends was Lord Byron you can find a good source in “Dear Harp of my Country” by James W. Flannery a book and two compact disks.

We must not forget Jane Austen’s letter (August 10, 1814) to Anna Austen who later became Anna Lefroy. “Let the Portmans go to Ireland; but as you know nothing of the manners there, you had better not go with them .” And this seems a good note on which to conclude, leaving Ireland and returning to Canada.

WORKS CITED

Austen, Jane. The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1933.

__________. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1997.

Austen-Leigh, William & Richard & Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: A Family Memoir. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1989.

Ball, F. Erlingtón. The Judges in Ireland, 1221-1921. London: John Murray, 1926.

Bartoletti, Susan Campbell. Black Potatoes, The Story of the Great Irish Famine 1845-1850. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001.

Berkeley, George & G. J. Warnock. The Principles of Human Knowledge; Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous. Cleveland: Meridian, 1963.

Cecil, David. A Portrait of Jane Austen. London: Constable, 1978.

Coohill, Joseph. Ireland, A Short History. Boston: One World, 2000.

Craig, Maurice. Dublin 1660-1860. The Chaucer Press, 1980.

Flannery, James. Dear Harp of my Country, The Irish Melodies of Thomas Moore. Nashville: J S Sanders, 1997.

Fitzgibbon, Constantine. Red Hand: The Ulster Colony. New York: Warner, 1973.

Harbison, Janet. “The Belfast Harpers Festival of 1792.” Ireland of the Welcomes March 1992: 18-22.

Hubback, J.H & Hubback, Edith. Austen’s Sailor Brothers. New York: John Lane, 1906.

Moody, T. W. & Martin, F. X. The Course of Irish History. Dublin: Mercier P, 1994.

O’Ferrell, Fergus. Daniel O’Connell. Dublin: Macmillan, 1981.

Ó’Murchú, Máirtín. The Irish Language. Dublin: Government of Ireland, 1985.

O’Tuama, Seán & Kinsella, Thomas. An Duanaire, 1600-1900: Poems of the Dispossessed. Mountrath Portlaoise: Dolmen P, 1981.

Reynolds, Mairéad. The Irish Post Office 1784-1984. Dublin: Government of Ireland, 1984.

Tomalin, Claire. Jane Austen, A Life. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

Wibberley, Leonard. The Good-Natured Man: A Portrait of Oliver Goldsmith. New York: William Morrow, 1979.

Copyright © 2002 by Joan Duffy Ghariani

Joan Duffy Ghariani was born and raised in Ireland and educated through Irish Gaelic and English. Joan passed away in September of 2003. She lived in San Francisco and was a bookseller and bookkeeper there. She was a frequent contributor at JASNA Northern California Region meetings. Many will miss her.